“Life is a Booleying…”

“Life is a booleying, death a going to the eternal home, and the booleying is to be spent in preparing stores which are to be enjoyed in the next world.” (1)

Pigeon Rock Valley, Galtee Mountains

Sunday 5th February 2023

Third Time Lucky

I sat on the hillside and looked out across the valley, following the stream as it meandered around the bend, and admiring the sun’s distribution of shine and shade across the slopes. All the while I munched down on my lunch rhythmically, like a cow. The lunch in question was a falafel and hummus wrap from Aldi (not quite like a cow then!), followed by a flapjack and a good helping of water.

Just below the frame in the image above was a narrow crumbling stone building. Just outside its bounds, I sat on the grass enjoying a well-earned lunch. I had already put some work in by that time, and my next move would be to head for home - completing a loop of sorts, and closing this mini-chapter spent in the western Galtees. If you’ve read the misfortunes of January in my previous post, this was the day it all came together.

To start with, it was a glorious day. The positive forecast which had teased me all week held fast. The anticipation of finishing what I had started last month hummed inside me. This was the view from our house that morning. A low fog lingered in the glen, but the mountains looked completely clear above:

View from the Front Garden

I won’t bore you with any of the same details as last time, but suffice to say that the parking spot was the same, not far outside Anglesborough, and the route up Temple Hill was the same as the failed effort last month. It was a completely different world this time, however, with no apprehension, no waiting and seeing what the weather will do. As soon as I had made the first ascent, reaching the crest of Paradise Hill, a previously-unseen view began to emerge.

Temple Hill (right) & Lyracappul (left)

I reached Shannaghaun Rock in good time - the spot where I had to abandon my last effort. The wind, though still noticeable on this fairly exposed strip, was much lighter than last time, and the simple fact of being able to see more than a few metres in front of you always helps. Disorientation resides in the mist.

Shannaghaun Rock, or “The Pinnacle”, en route up Temple Hill

On the left as you walk towards Shannaghaun Rock is a fairly steep drop-off, though it’s definitely not as menacing as my mind was led to believe during the foggy, windy conditions last time out - I guess that’s a good little safety feature in the human brain! Beyond the immediate fall-off, the ominous slopes of Temple Hill catch the eye, as you can see below.

The Punishing Slopes of Temple Hill

Having left “The Pinnacle” behind me, I was on new ground. As it turns out, the reassurance I had gotten from my fellow climbers last time about how the worst is behind you at this stage, and the rest isn’t so bad, was debatable. There was a short distance remaining, but still a tough, extremely steep final ascent. The adrenaline of finally reaching the top of this mountain drove me on. As I progressed up the final stint, the clearness of the day started to dilute, muddied by streaky wisps of fog. It was by no means dense, but a notable shift nonetheless. It never ceases to amaze me how the tops of mountains have their own micro-climates, and things begin to change in just a few steps.

When I had finally reached something of a plateau, I turned north towards the summit. My climbing was done - just a short amble to the Trig Pillar denoting Temple Hill’s highest point. As I approached, it was buried in fog, and a cold breeze was shooting across me from the west. The image below is heavily edited to pierce through the fog, but it was quite thick to the naked eye.

The Foggy Summit of Temple Hill

It was my hope that I’d have an awesome view across to Lyracappul and beyond from this vantage point, and could get some scenic images of the Galtee peaks from a new angle. On a clear day like today? Surely!

Frustratingly, the fog hanging over me at that time obscured my view of the peak opposite, and I could only just make out the foothills below. I was fully aware that, at that precise moment, it was nothing short of a beautiful day all around me except for exactly where I stood and perhaps the handful of other Galtee peaks above the 700 metre mark. It was this knowledge that kept me there, waiting, for about forty-five minutes. I was sure the fog would lift, and a stunning world would reveal itself. Sadly, it did not, and conditions were very cold with the sun’s glow blocked. Temperatures were actually in the minus figures on the summit. I had to move off, lose some elevation, and get the sun’s rays back on me.

Pigeon Rock Valley

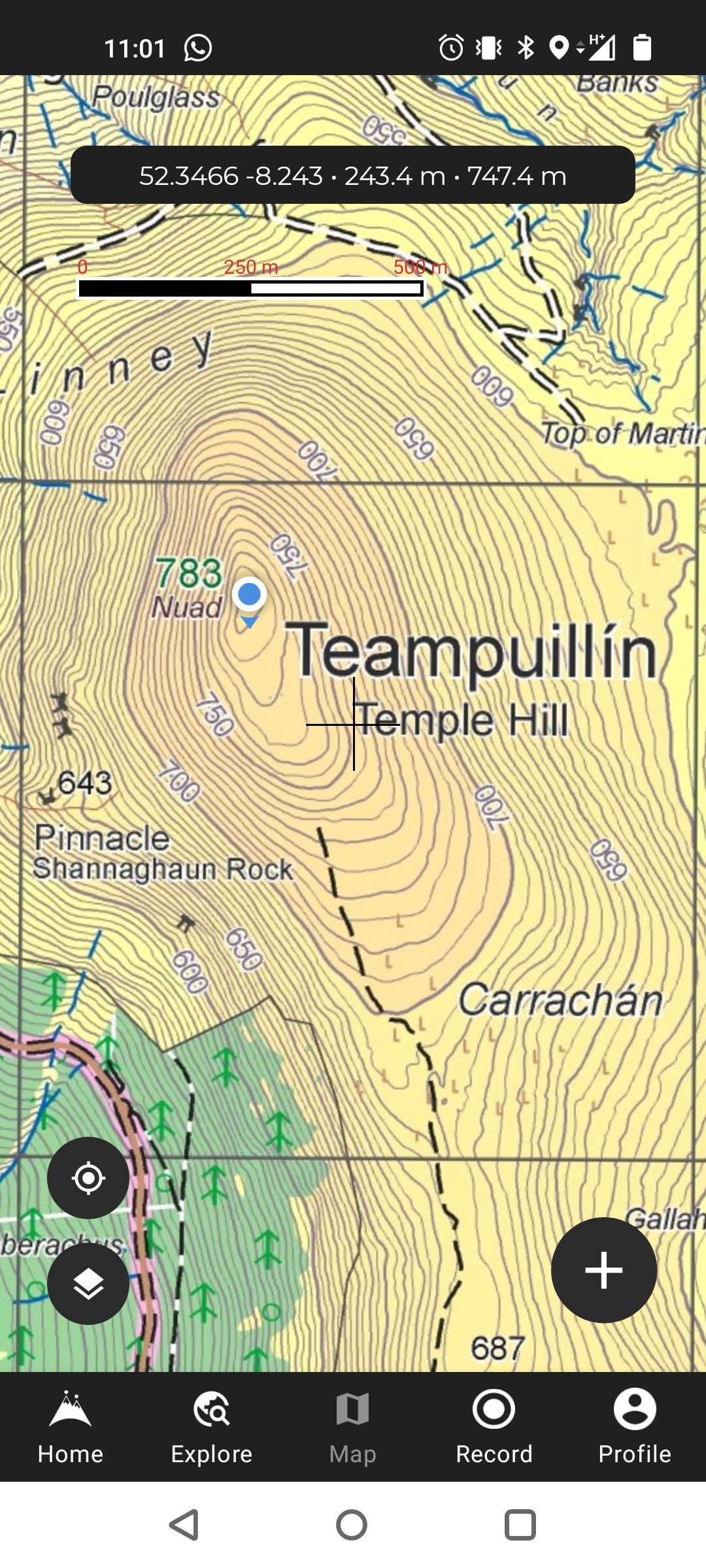

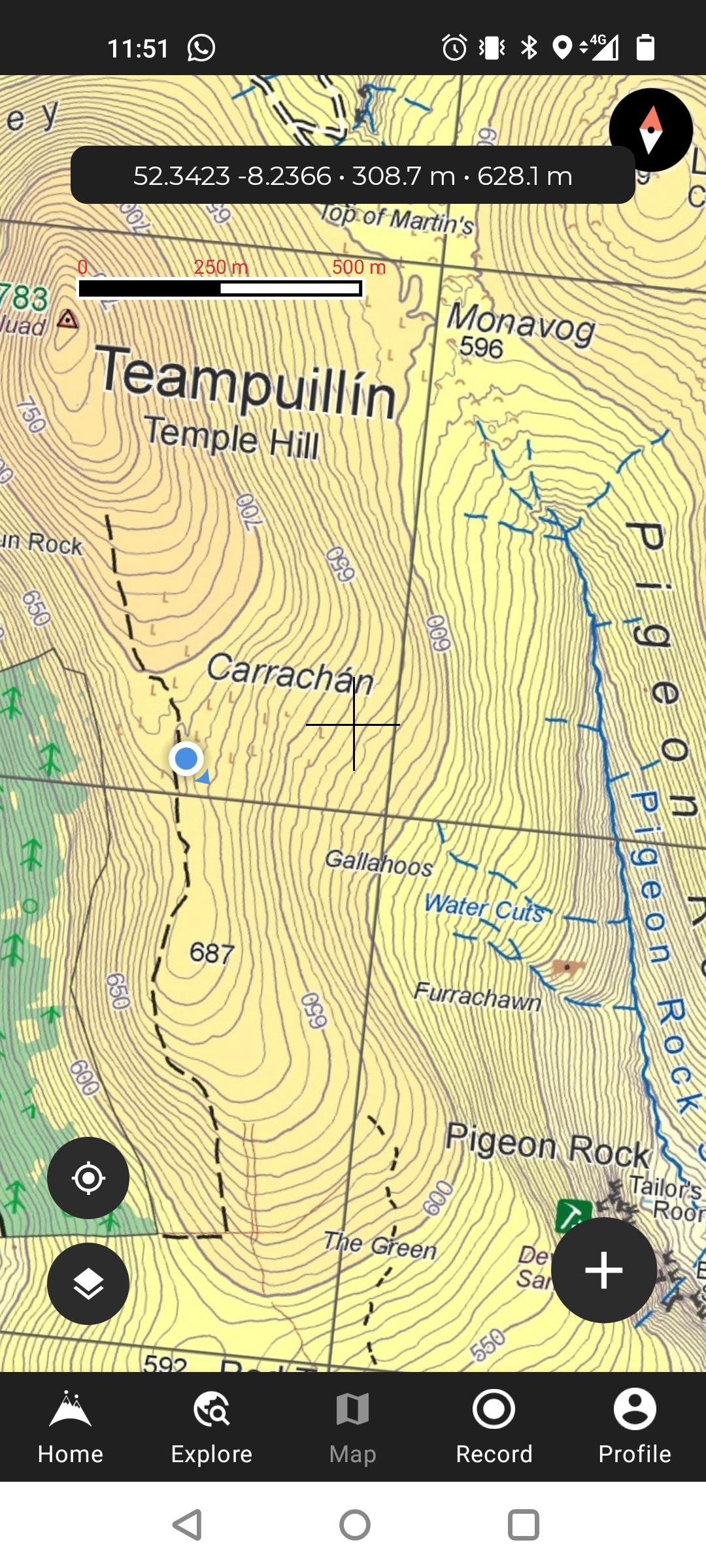

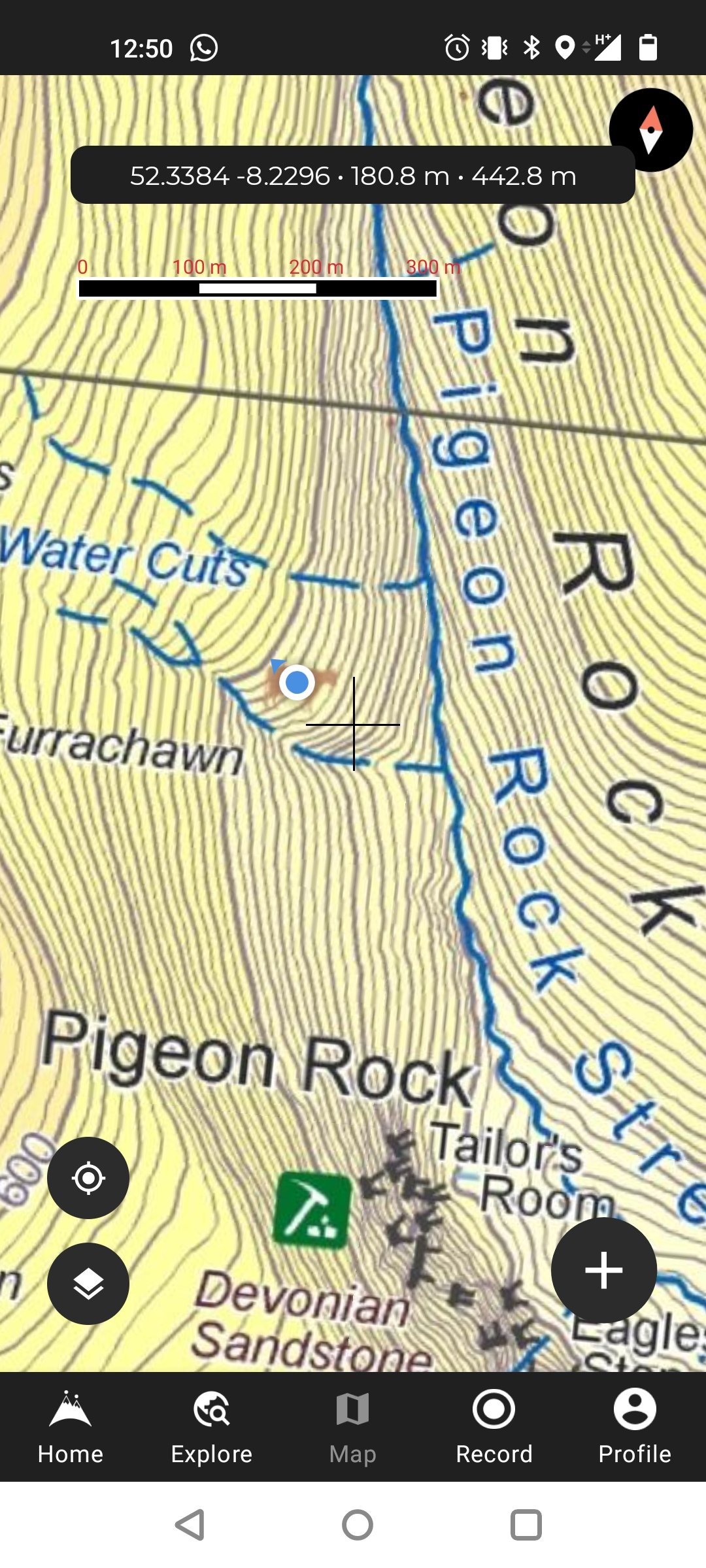

From Temple Hill I had planned a route southeast to a marked booley site (denoted by a brown cow). I would gently descend in that direction for about 1km before ultimately veering a full 90° east. As you’ll see in the map sequence below, once I had descended to about the 690 metre mark along the “shoulder” (again, please don’t take my use of that word as necessarily accurate), the move east to the marked booley site in Pigeon Rock Valley would involve a sudden and steep descent. I would be dropping about 200 metres of elevation - always a hard decision to make having worked so hard to gain it!

Naturally, once I had moved off the summit and wandered some way south, the fog appeared to lift off the peaks in spells. A tinge of regret resonated in the back of my mind that I was missing (at the very least) periodic views up there. What can you do? You can’t sit up there freezing until it clears, certainly not when you’ve got much more planned for the day. Here’s an image looking back at Lyracappul as its summit seemed to have almost cleared.

A Circle of Stones, and Lyracappul Behind

As you may have noticed in the maps above, the booley site is guarded between and behind some water cuts. This meant I had to carefully navigate to make sure I was on the right side of the southernmost cut. That said, once I had arrived on the scene it became apparent that it would have been possible to cross these deep cuts in places if I needed to.

Earlier in this piece I mentioned the remains of a stone structure, just outside which I had rested for lunch. The building in question is, of course, the booley site. I’m sure you’ll agree its perch is fairly impressive, on the crest of a hill overlooking Pigeon Rock Stream. Truly an amazing viewpoint. I stayed there sitting and soaking it in for longer than I had planned, before finally taking out the camera.

Booley site overlooking Pigeon Rock Valley

The building is narrower than nearby Moonacoon house, visited last month. It doesn’t strike me as large enough to be a living space for humans. Might it be an enclosure for livestock? I’m not convinced it’s large enough for that either, but this is where I have to call into question my twenty-first century biases. To what extent is my understanding of a cramped space different to the understanding of eighteenth or nineteenth century upland herders? In his book Transhumance and the Making of Ireland's Uplands, 1550-1900, Eugene Costello identifies “thirty-two archaeological sites with evidence of pre-twentieth century occupation or stock management” in the Galtees. Of those thirty-two sites, Costello says “two discrete livestock enclosures were identified”, while “the other thirty sites are structures formerly used for human shelter and/or habitation.” (2) Have I visited one of only two specifically designated animal enclosures in the Galtees? It seems unlikely.

If this building is indeed too small for human use, might that indicate that there were other larger buildings nearby to serve housing needs? This is where my not being an archaeologist lets me down. I don’t have the ability to read the landscape and observe its clues in a way that a trained professional might. I studied history - not archaeology - at university, meaning I’m more comfortable gleaning information from books and journals than from the land itself.

I haven’t found any information particular to this site yet, but that’s not to say I’ve made no progress on the research front. In fact, I’ve managed to get my hands on a few interesting sources. When my January blog was posted, a very well-read woman with a keen interest in booleying got in touch to point me in the direction of some useful sources, for which I’m hugely grateful! Through the Tipperary Studies branch of the Tipperary Libraries service, I was then provided with electronic copies of these sources. I’m omitting names for anonymity purposes, but again the person I spoke with in the Thurles library was really helpful and patient over the phone. Thank you to both women for your guidance and assistance.

A closer look at the booley

Michael Cunningham's Recollections

One of the sources I got my hands on was a 1945 article entitled Traces of the Buaile in the Galtee Mountains. In the article, Caoimhghín ua Danachair presents the testimony of a local man who remembered the system of booleying at work here in the Knocknascrow area. The man’s name was Michael Cunningham and he was eighty years old when he spoke with the author in 1940. Cunningham recalls his personal involvement in booleying some sixty-five years previously (in about 1875). Invaluably, his recollections are included verbatim:

“Comaointeas is what we used to call this going up on the mountain with the cattle in the old times. All the mountain was held as commonage by a number of people who lived at the foot of the mountain, and they used to send the cattle up in Spring and bring them down again in the Autumn. About the middle of April was the time they started to go up to the buaile, as we used to call the house, and they would bring them down again at the beginning of November. The reason for going up at all was that there was no rent on the mountain and the land on the farm below was nearly all put under hay to feed the cows in the winter time. In that way a farmer could have a lot more cattle on a small farm. There used to be a house at the buaile, and some of the family used to spend the whole summer above with the cattle. Sometimes it was the young ones that went up, and some times it was the old people, if there was a lot of work to be done below, and they wanted the young people there to do it. They would live in the houses on the mountain all the summer and only come down to Mass and when they were bringing the butter. About from twenty to forty cattle each one would have on the mountain. The houses were by themselves with a mile or more between them, so that it was kind of lonely sometimes up there, but other times they would come together and have a dance or some other fun like that.

The work they did was to milk the cattle morning and night and make the butter. When enough of it was made they brought it down to the road to be carried to the town (i.e. Mitchelstown). They would bring it down the mountain in firkins that the cooper used to make, for in those times the cooper was an important tradesman in the district, and he got plenty to do.

In May they used to plant potatoes up on the mountain near the buaile. 'Black potatoes' we used to call them, and I used to hear the old people saying that the blight never came on them until the Famine year. They used to cut the green stalks and feed them to the cattle, and it would be nearly November when they dug the last of the potatoes on the mountain. Potatoes and buttermilk they used to eat mostly, and they had the fresh milk and the butter and oaten meal bread, and, I hear, an odd drop of poitín.

What stopped the comaointeas in this district was this: as long as the mountain was rent-free it paid the mountain farmers to send up the cattle, but about sixty five years ago, or maybe a little bit more, the landlord of the place, old Kingston of Mitchelstown, put a rent of three pounds a head on every cow that was on his tenants' land, and of course that took away whatever profit the farmers had out of the comaointeas. The cows were taken away from any one that did not pay the new rent and put in the pound, and sold off if they were not paid for. That was not so easy to do, because the farmers would not bring in the cattle and the 'wattle men' had to go out on the mountain themselves and catch the cattle. But in a short time all the cattle were seized, or sold by the farmers because they could not pay the new rent, and from that time on they kept only as many cattle as they could feed on their own farms." (3)

Home via Knocknascrow

To top off the day’s adventures, I would close it into a loop. From the booley in Pigeon Rock Valley, I had planned a route south and then southwest. This heading would take me past Moonacoon House once again, before heading for home. I wasn’t overly pleased with the photographic results of my last trip there, rushed as I was with the cold and miserable weather. I hoped I could produce better pictures today.

It was an almighty struggle to clamber my way back up to 600 metres, especially with all that food in my belly! Once I had reached the 600 metre mark above the water cuts, I turned south and contoured around the steep slopes in a southwesterly direction, eventually curving around onto an open soggy plain across which Moonacoon house sat sheltered behind a gentle slope. It was a relaxing amble across a relatively flat expanse. I was glad of it after the extremes of the day's climbing up until that point.

I am happier with the image below than those captured last time, but still not enamoured. I’m probably my own harshest critic, but I’m certain that a moody picture taken in the golden hour before sunset would induce more magical results. I’m sure I will be back again in different light.

Moonacoon House, Knocknascrow, Galtee Mountains

If I’ve read him correctly, Costello suggests that the mound of stones you see in the left foreground of the image above (the southeastern corner of the building) may have been a storage space for butter produced during summer herding. The main three economic exploits of booleying in this region seem to have been, first and foremost, butter production, followed and supported at different stages by the secondary practices of peat cutting and/or the growing of potatoes. Michael Cunningham already told us about the potatoes in his recollections. On peat cutting, Costello notes that “many disused trackways run up the slopes towards these bogs, where peat-cutting was continued by hill farmers until the middle of the twentieth century.” (4) I definitely have in mind to photograph some of these trackways in the coming months.

When you think about booleying as a variable and all-encompassing practice, incorporating a variety of economic activities beyond the mere milking of cows, the benefits seem even more obvious. Before the rents that Michael Cunningham mentioned were introduced in the latter half of the nineteenth century, there must have been great incentives to sending herders into the uplands for the summer, essentially expanding the space you had to work with on a temporary basis, taking advantage of the growth and conditions at higher altitudes, and potentially adding a supplementary income stream like peat. The benefits come into even sharper focus when you consider that many farmers sent the younger members of their family to do this seasonal work, which allowed the farmer himself to stay at home and continue managing the day-to-day.

Life is a Booleying

I’m grateful that you’ve read this far. Thanks for spending your time here. I’ve now installed a comments section at the bottom of these blog posts, so please feel free to jump down there and share your thoughts and feedback.

I began this post with a quote from Geoffrey Keating’s work, Trí Bior-Ghaoithe an Bháis, which I stumbled upon in Pádraig Ó Moghráin’s article, More Notes on the ‘“Buaile”. The quote reads,

“Life is a booleying, death a going to the eternal home, and the booleying is to be spent in preparing stores which are to be enjoyed in the next world.”

I was moved by the poetry of this line. I love how it frames booleying as being symbolic of the work and play of life, a temporary activity in a temporary home here on earth, while returning to the homestead represents eternity.

I would like to dedicate this piece to my uncle Eamon (Eddie) Commins, who went to his eternal home on February 15th 2023. May he rest in peace.

Sources

(1) More Notes on the "Buaile" (Pádraig Ó Moghráin and S. Ó D.) in Béaloideas , Jun. - Dec., 1944, Iml. 14, Uimh 1/2, p. 46. Published by An Cumann Le Béaloideas Éireann/Folklore of Ireland Society.

(2) Costello, Eugene. Transhumance and the Making of Ireland's Uplands, 1550-1900. Available from: VitalSource Bookshelf, Ingram Publisher Services UK- Academic, 2020. p. 108-109.

(3) Traces of the Buaile in the Galtee Mountains (Caoimhghín ua Danachair) in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Dec., 1945, Vol. 75, No. 4 (Dec., 1945), p. 250. Published by Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.

(4) Costello, Eugene. Transhumance and the Making of Ireland's Uplands, 1550-1900. Available from: VitalSource Bookshelf, Ingram Publisher Services UK- Academic, 2020. p. 122.

Never miss a blog post! Subscribe to my mailing list and have it come straight to your inbox.