Renovator of the World

“Three renovators of the world : the womb of woman, a cow’s udder, a smith’s moulding-block.” (1)

The Primordial Renovator

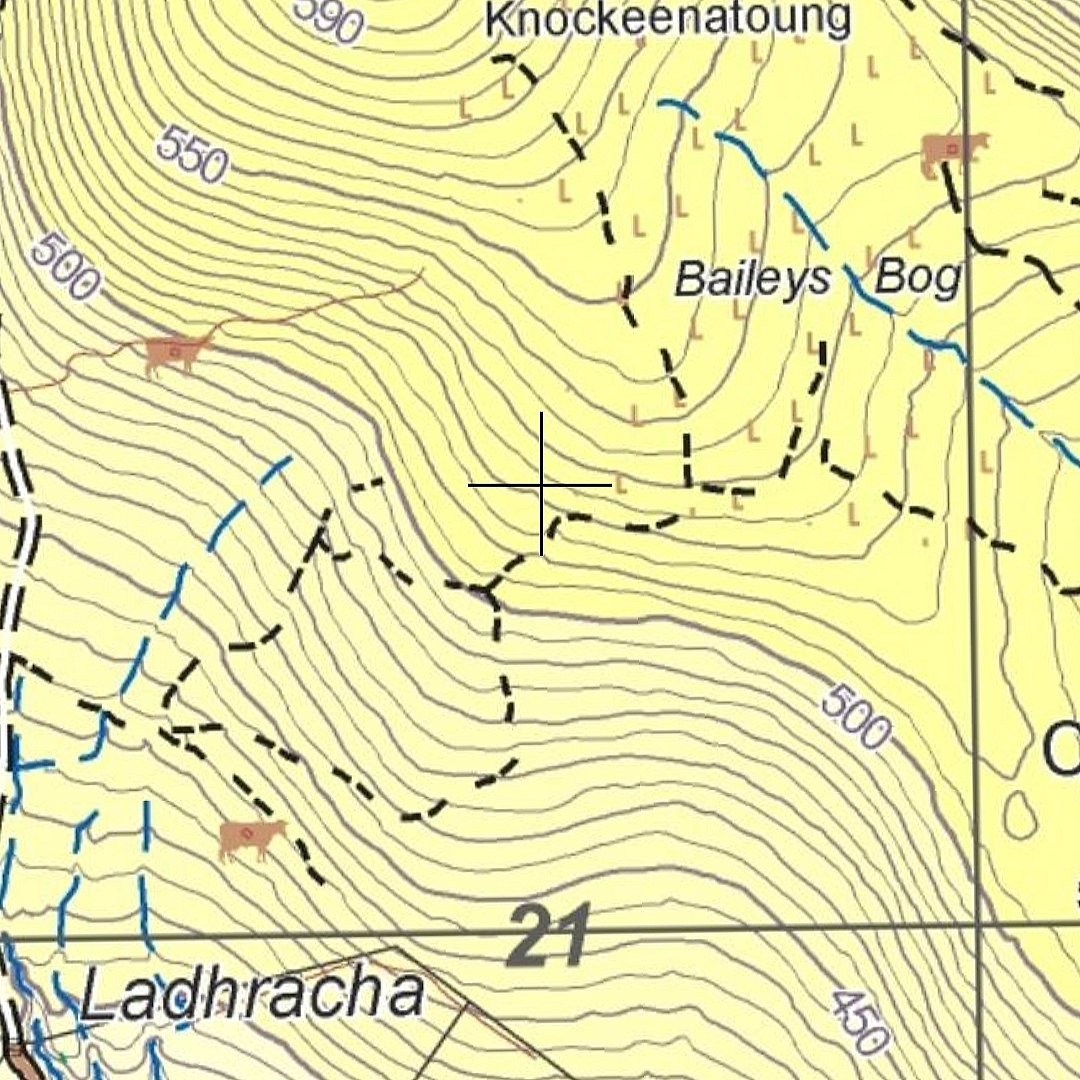

In the 1km by 1km square of map above, you’ll notice three of our bovine friends in relatively close proximity, denoting booley sites. This small area of mountain on the southern side of the Galtees was the primary focus of my adventures in March. Before we get to all that though, can we chat about our steadfast companions?

The quote above, borrowed from The Triads of Ireland, places cows on an equal pedestal to a woman’s womb and a blacksmith’s forge. All three things are presented as creators, or “renovators”, bringing something new into the world. Something born. Something forged. Or something splashing with a shallow tinny sound at the bottom of a bucket.

The Triads have been translated from Irish and passed down to us from nine separate manuscripts dating from the fourteenth to the nineteenth century. They are essentially short social and philosophical musings presented in threes, and they offer intriguing insights into the ways of thinking of the times in which they were written. The cow features in quite a few of them, and that’s telling as to the importance of the animal in medieval and early modern Ireland. Here’s another:

“Three slender things that best support the world: the slender stream of milk from the cow’s dug into the pail, the slender blade of green corn upon the ground, the slender thread over the hand of a skilled woman.” (2)

The same themes rise to the surface throughout the texts. The cow as a primordial driver of life and sustenance. Womanhood. The blacksmith’s forge. The feeling of plenty instilled by a successful crop and harvest. Those four themes rotate in and out of the two quotes above, and here’s another example:

“Three sounds of increase: the lowing of a cow in milk, the din of a smithy, the swish of a plough.” (3)

I was introduced to this unusual book thanks to an episode entitled “The Cow in Folk Tradition” on the Irish folklore podcast Blúiríní Béaloidis. The podcast is presented by Jonny Dillon and Claire Doohan in the National Folklore Collection in University College Dublin. Here is a link to the episode on cows in folk tradition: Listen Here

Dillon and Doohan portray the cow as central to past Irish societies. In a spiritual sense, the cow as a goddess figure seems to originate in India and move with the expansion of Indo-European culture, all the way to Ireland. The animal was later linked to Saint Brigid (patron saint of fertility among other things). Several stories tell of Brigid travelling in the company of cows, and there are fresco paintings in England which show her milking a cow. As well as fertility and the keeping of cows, she is also linked with smithing and the harvest - in other words, all four of the themes which weave in and out of the Triads shared earlier.

Though the spiritual background is interesting, I find the cow’s more tangible involvement in Irish society even more intriguing. In terms of the animal’s basic function, it was not merely milk (and resulting butter) that they provided. The UCD folklorists point out that even the urine and excrement had its uses. Cow’s urine would have been used in acts of divination (which lends further weight to the spiritual significance of the cow), while the dung would often be used as a fertilizer.

The old Irish Law Tracts reveal that cows were used as “currency, barter and tribute.” If an honour price was to be paid for a wrongdoing, cows were often the currency. It seems clear that the animal commanded a degree of respect too, and there is evidence for this in the Law Tracts. If a person was attacked by a bull during mating season, for example, it was deemed to be the victim’s own fault for being near the bull during that season and the owner of the bull may face no punishment. Even the names of men at various socio-economic levels had titles relating to cows like “Cow Lord”, which would have been a nobleman with a certain amount of cattle. (4)

Nowadays, our bovine friends live down in the lowlands and the flatlands with us. Since the 19th century, sheep (our ovine friends!) have replaced them in upland areas. Incidentally, these ovine friends decided to make a few guest appearances in the images I produced this month, as you’ll see later in this piece.

Knockeenatoung

Sunday 19th March 2023

I live pretty much on the opposite side of the mountains to Coolagarronroe, which is where the hill of Knockeenatoung is located. As with all of my hikes on the Galtee’s southern slopes, I had to drive around the range first. It was just over a half hour’s drive.

I had decided to start early. I parked the car at 8:45 at a small lay-by on the Black Road, and began the gentle climb north. The weather forecast warned of wetter conditions from about midday onwards, so I wanted to have the majority of my rambling done by then.

The day’s sites were much more accessible than some of the previous ones I had visited. I only had to walk a kilometre or so from the car to the first one. Once I had travelled that distance I came off the path and veered east towards the first brown cow marked on my map. My divergence seemed to concern two fellow walkers as they called after me to check that I knew where I was going. I certainly did.

Lower booley site in Coolagarronroe.

The trail I had come off is just about visible as a horizontal line in the background of the image above. And in terms of map location, this site is the cow marked on the bottom left of the map section I shared earlier. As you’ll notice by the broken black lines on the map, some trails skirt closely by this site, and there are water cuts between it and the main path I had come from.

After I had made a number of pictures here, I followed the trail northwest until I had crossed back across the water cut, and then directed north towards the next marked site, located at just under 500 metres. I would only have to gain about 70 metres of elevation to reach it. The climbing so far was nothing too strenuous. I had a drop of water and a flapjack on my way to the next location.

The second spot, perched as it was at a slightly higher altitude, had more impressive views and was more approachable in terms of photographic composition. It wasn’t just its perch which helped in this regard, but the surrounding features also told a story. There was a ready water source nearby, invariably the case at boolies. There is also what seems to be a peat trackway, which starts its journey at “Bailey’s Bog” and weaves its way past the booley site in a southwesterly direction, ultimately rejoining the Black Road. It shows all the signs of being a route for the transportation of peat, perhaps by those staying in the summer booley, and I believe that brown trail lines like those illustrated on the map are generally relating to peat.

Peat trackway on Knockeenatoung? Featuring a friend.

A bend in the trackway.

Thankfully, there were more features to work with here in composing a photograph, which allowed me to situate the site in a wider context, presenting it as part of the landscape with a sense of interconnectedness, rather than just a pile of stones plonked in the middle of nowhere.

Booley site and stream.

Ok, this one still looks like a pile of stones plonked in the middle of nowhere.

Once I’d gotten a number of images I was happy with, I headed NNE towards the summit of Knockeenatoung. A gentle strain on the calves, but given the booley I had just departed was at about 500m, I hadn’t much climbing left. The summit of Knockeenatoung stands at a modest 601m. The heart rate creeped into threshold and my breathing deepened. In a few minutes I had made it.

It was my first time on this summit and I found not only a cairn but a doorless stone building there too. I’m not sure about its purpose.

It was very soon after the image above that I felt the rain coming on and the wind seemed to stir up a little. It wasn’t far away from noon and the predicted bad weather was arriving right on cue. Though I had some waterproof gear with me, my trousers weren’t. I decided that my day’s work was done, that I was going to get down off this rock, and the other two booleys further east would still be there next weekend.

I descended down the very steep north face of the hill, towards the Aircrash Memorial. On the way down the slope, the view across to Galtymore was a new one for me, with the black road meandering towards it. In the image below you can actually see the Aircrash Memorial (if you squint) on the right side of the triangle of pathway in the centre foreground.

Back on relatively flat land, I allowed myself a few moments to take in the memorial, though I had been there a few times before. It’s written in white on a black marble-like plaque and commemorates “airmen Timmy Byrne, Tom Gannon, Dick O’Reilly, founder members of Abbeyshrule Aero Club Co. Longford, who lost their lives on these mountains on the 20th of September 1976.”

From here I was able to rejoin the main path and head south back towards the car. It was about 2km back on a gentle descent. Luckily, the rain was also gentle for the moment, albeit consistent all the way to the car. I had only just sat back into it, boots off and wet gear changed, when the heavy rain started up and pounded on the windscreen, my warm body steaming the glass on the inside. A narrow escape.

Coolagarronroe Revisited (featuring sun!)

Saturday 25th March 2023

Map screenshot showing all four boolies in Coolagarronroe.

In the map above you can see the two booley sites visited last weekend on the left side. In the centre of the image, and northeast of that, are the two other boolies which I would be visiting this morning. Time to finish the job we started last weekend.

There are some sentences that only photographers speak. One example is, “it’s too nice a day today,” and I must confess this thought did cross my mind as the sun glared down on my back on the Knockeenatoung hillside. It’s just too harsh a light to work with when the sun reaches us unobstructed, and I’ve never liked the contrasty look that goes with it. In a studio environment, photographers use things called soft boxes to soften the light of the studio lights. I’ve often thought that a cloud is like nature’s very own soft box, softening the light and allowing a broad and subtle palette of colours to show themselves in the landscape. The morning of the 25th of March was an absolute dream for a landscape photographer. There was enough brightness from the sun to give the images life and vibrancy, but the sun’s rays were regularly punctuated by clouds, and very often you’d get these shadows creeping like water across the slopes as clouds moved between the sun and the earth. This meant the scenes were often dynamic, and I would have to change my exposure settings drastically just a few seconds apart, depending on what the clouds were doing. So, allow me to correct my earlier thought and say that it was actually a perfect day for image-making.

To reach the first of the remaining two boolies, today’s plan was to follow the Black Road until I reached the peat trackway, which passes by one of last week’s boolies, as you’ll recall. I decided to walk up through the trackway because, directionally, it more or less led straight to today’s first destination - a third booley located in Bailey’s Bog. Trudging uphill through the trackway gave me pause to think about the labour involved in moving peat across the uplands. I’m sure lots of stones have fallen into the trench since it was used for transportation purposes, but it did seem like a lumpy enough trackway. I did not climb up out of the trench, but stayed within its bounds until it disappeared and merged with the open mountain.

Eventually I was bounding across something like flat land, though it was boggy and treacherous underfoot, and after a short journey I had reached the booley in Bailey’s Bog. It looked small enough, and circular compared with the larger rectangular ones seen earlier. Evidently not a building where the herders lay down their weary heads. I wonder what its use might have been.

Booley in Bailey’s Bog, Coolagarronroe

As you can see below, the sheep had seen enough and weren’t overly pleased by my hanging around at the booley.

The sheep had seen enough.

Did you notice the stray wool on the rocks by the way? Have a closer look in the image below. I’m left wondering if the sheep have been getting a cheeky back or neck rub on these rocks?

Sheep wool on the booley rocks

I got images I was happy with unusually quickly and efficiently on this occasion, so it was on to the next one. I strode across to the “edge” of the shoulder I was on and looked out across the valley beneath me (Gaddee Glen, according to the map). The view of the mountains opposite was stunning, as you can see in the image below. This is a phone picture by the way, as is the one after it, just in case you note any poor image quality.

View on the other side of Gaddee Glen

The descent from the Knockeenatoung shoulder down to this final booley was sharp, as you can tell by the narrowness of the contour lines in the map above. It was also quite slippery. A lot of care was needed in navigating downwards, zig-zagging rather than moving in straight lines, and trying to avoid the wetter patches where possible. Once I had reached the trackway in the image below, the booley was just a few steps further.

Trackway near the fourth booley

It’s not often I can say this with such clarity and without caveats, but I am absolutely in love with the two images I’m about to share with you below. They are up there with my favourite images. And I love the fact that the sheep stood in for the second one. And stayed there for quite some time too! I took a number of versions of this image, moving around and changing perspectives. The sheep was simply not bothered and stood there stoically as I did my weird human activity.

Booley in Gaddee Glen

Booley in Gaddee Glen, featuring a friend

Unfortunately, there is one thing missing from these images, and that’s our bovine friends themselves. Notable in their absence, it must be said, but look at the history they have left behind in our uplands. Look at the lasting marks on the landscape. The circles of stone. The rectangles. The walls and enclosures. The trails and trackways that sidle by the booleys. And look at the strange man who keeps coming back into the hills with his silly equipment to see what they’ve left behind. They certainly seem to have made a considerable impression on him.

Looking back at the map now, I get to thinking about the brown cows that have been drawing me into the mountains these past few months. On the map, just a relatively featureless illustration. Beyond the illustration, though, there is a rich and textured tapestry of our social history - one that I’m grateful to have the opportunity to explore.

—

Thank you for reading! I’d really value your comments or feedback in the comments section below. Hopefully, some of you are coming along with me in this project and I’m sure you could offer fresh perspectives. I hope you have a great month and see you at the end of April for the next edition.

All the best.

Alan.

The ever glorious Galtymore

Sources

(1) Meyer, Kuno, ed. (1906), "The Triads of Ireland", Todd Lecture Series, Hodges, Figgis, & Co, Dublin; Williams & Northgate, London, no. 13. p. 21

(2) Meyer, Kuno, ed. (1906), "The Triads of Ireland", Todd Lecture Series, Hodges, Figgis, & Co, Dublin; Williams & Northgate, London, no. 13. p. 11

(3) Meyer, Kuno, ed. (1906), "The Triads of Ireland", Todd Lecture Series, Hodges, Figgis, & Co, Dublin; Williams & Northgate, London, no. 13. p. 19

(4) Dillon, J. & Doohan, C. (2018 The National Folklore Collection) Bluiríní Béaloidis. [The Cow in Folk Tradition]. January 2018.

—

Never miss a blog post! Subscribe to my mailing list and have it come straight to your inbox.