From a Pen, Into the Hills

The Glen of Aherlow from the summit of Cush

24th April 2023

Cush on a Sunny Evening

April was a busy month, not only for work reasons but also my social life. A two-day stag, a trip to a Champions League tie, a Munster hurling match, board games with friends, to name just a few. I had a lot of fun! Unfortunately, it did mean that I wasn’t able to get into the mountains until the end of the month. On the 24th of April, I worked from home. Once I had logged off, just after 5pm, I headed straight to the Cush car park, about five minutes from home. I had pre-packed my bag the night before with the express intention of making better use of the extended evenings.

The plan was to tackle Cush from its eastern side rather than the more direct (and notoriously steep) route. This wasn’t out of laziness. Being the closest Galtee peak to my home, I have climbed Cush in the traditional way many times. However, I noticed that the map showed a booley site nestled into the eastern shoulder of the mountain. The brown cow icon didn’t have a black rectangle inside it, meaning it wasn’t going to be any kind of walled structure, rather a more subtle disturbance in the landscape - trace evidence which may require a careful reading. In fact, there was a good chance there would be very little to see at all, but it was worth investigation nonetheless.

When I arrived at the location marked on the map, I found a dry earthen patch with rocks protruding from a steep embankment on the side of the hill. Without the skills of a historian or archaeologist, there was very little to work with, both in terms of deciphering what kind of evidence I was actually looking at, and also how best to photograph it. I didn’t manage to get any images of note.

I was determined to make something of the evening hike, so I didn’t spend much time pondering. Instead, I decided to push on towards the summit of Cush in the hope that I would get there in time to make use of the golden hour before sunset. It was more tiring than I had anticipated progressing up the shoulder, as it was quite boggy underfoot and there were a number of peat banks to navigate around. When I reached the summit, it proved to be a worthwhile effort, as you can see in the images above and below.

The Glen of Aherlow from the summit of Cush

A Stump in Glen Cush, taken from the summit of Cush

With the light now fading, the temperatures dropped. I descended down the steep face of Cush, managing my steps carefully until the harsh gradient levelled out somewhat. As I headed back towards the Upper Cush Stile, I passed a number of lambs springing along near their mothers. At one stage I almost accidentally walked into the space between a mother and its lamb, but as soon as I realised I was entering into such a no-mans land, I stepped back, flanked around and gave them a wide berth. As I walked away I cast a glance over my shoulder. The lamb had scurried back to safety, and its mother led it away into the scrub. It was heartwarming to witness the magnetism between the lambs and their mothers. The beauty of innocence, and the power in the heart of those who’ll protect it.

30th April 2023

Boolakennedy (Buaile Uí Chinnéide)

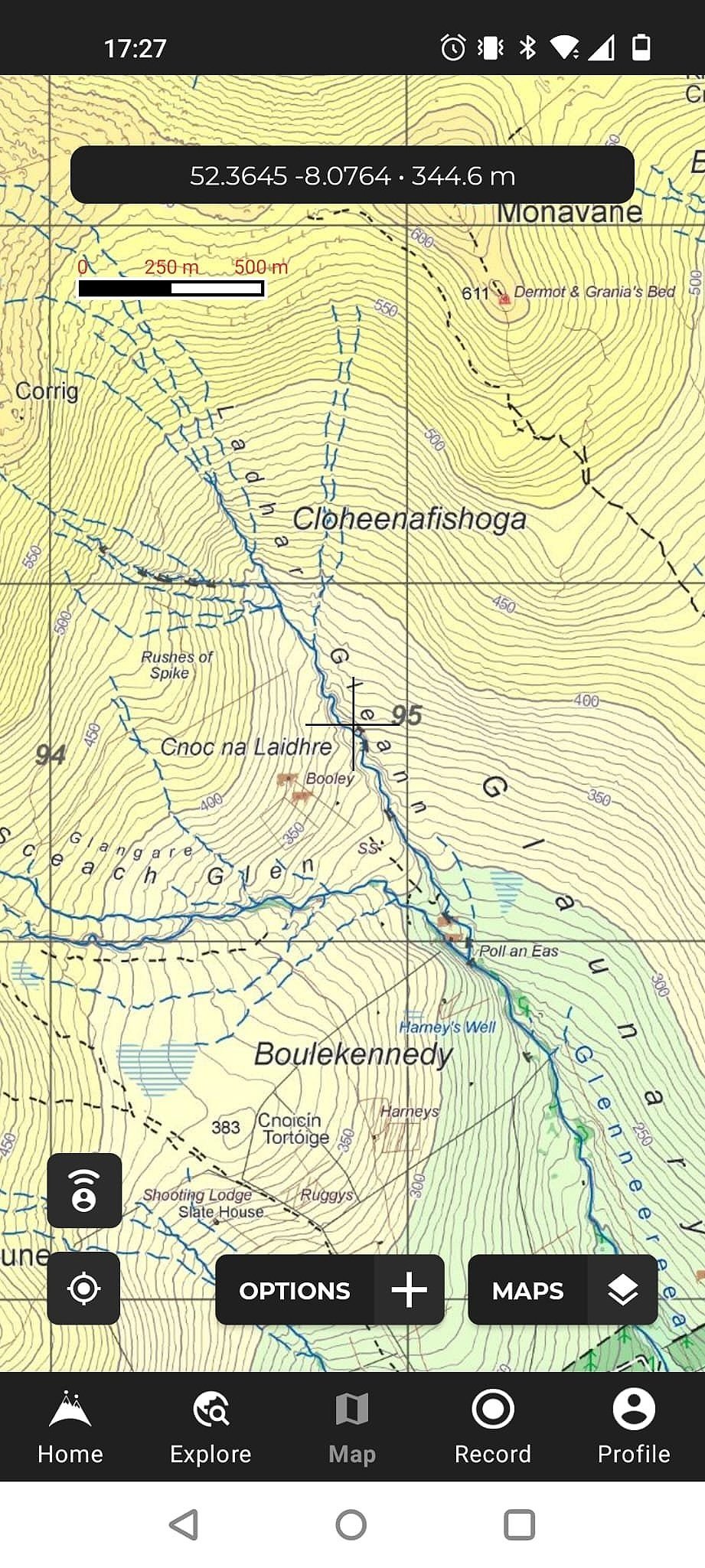

To close out April, I drew up plans for a trek into the eastern Galtees, in pursuit of a few booley sites in close proximity to one another. The sites were in and around an area called Boolakennedy. You don’t need to be a genius to work out why a placename like that piqued my interest. The Irish version translates directly to “Kennedy’s Booley”. It’s not the first time I’ve seen an area’s history of booleying built into its placename. In the westernmost end of the Galtees, near Temple Hill, there is also a place called Boolalisheen. I’m fascinated by the little threads of history that can be gleaned just from a placename alone, but more on that shortly!

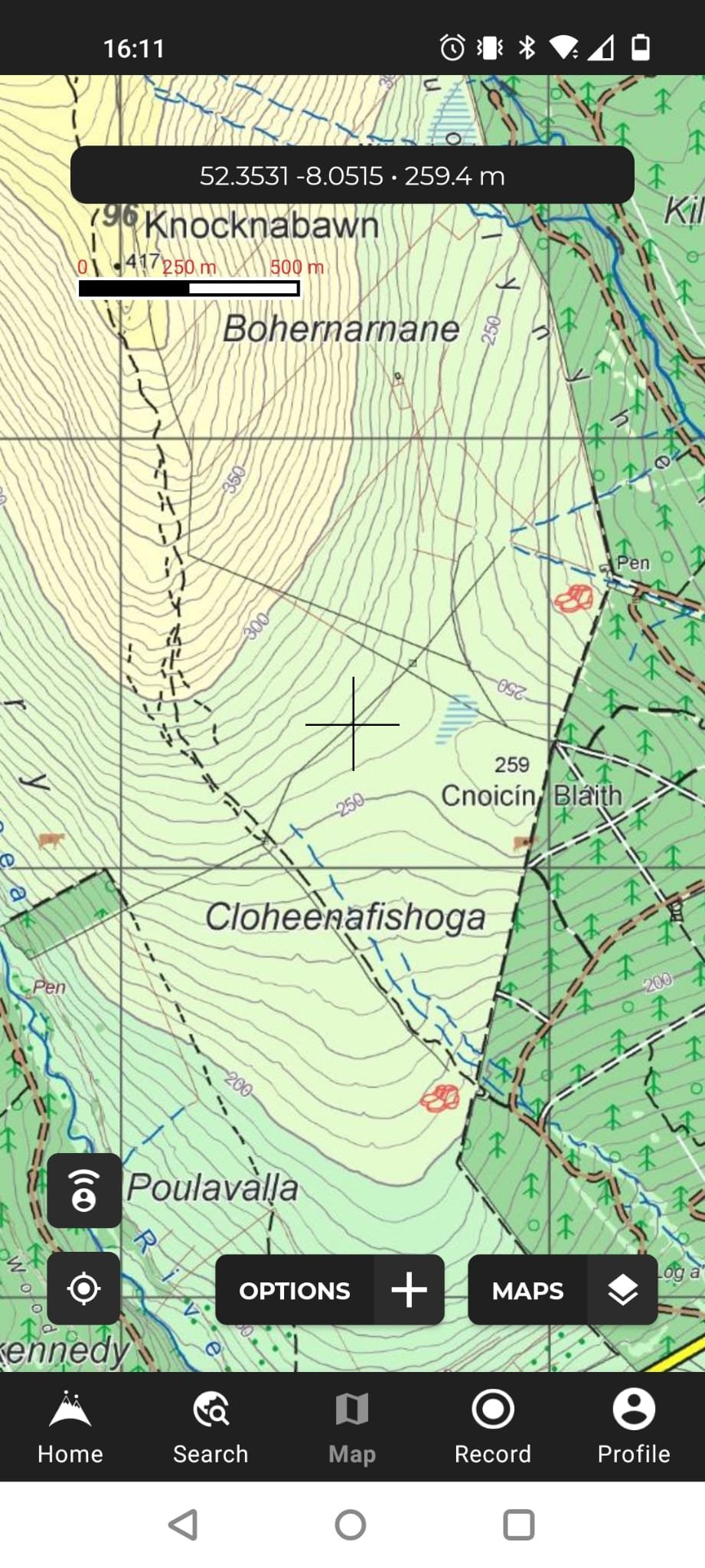

Firstly, let’s get to the day’s walking. Here’s a screenshot of the overall area I was set to explore:

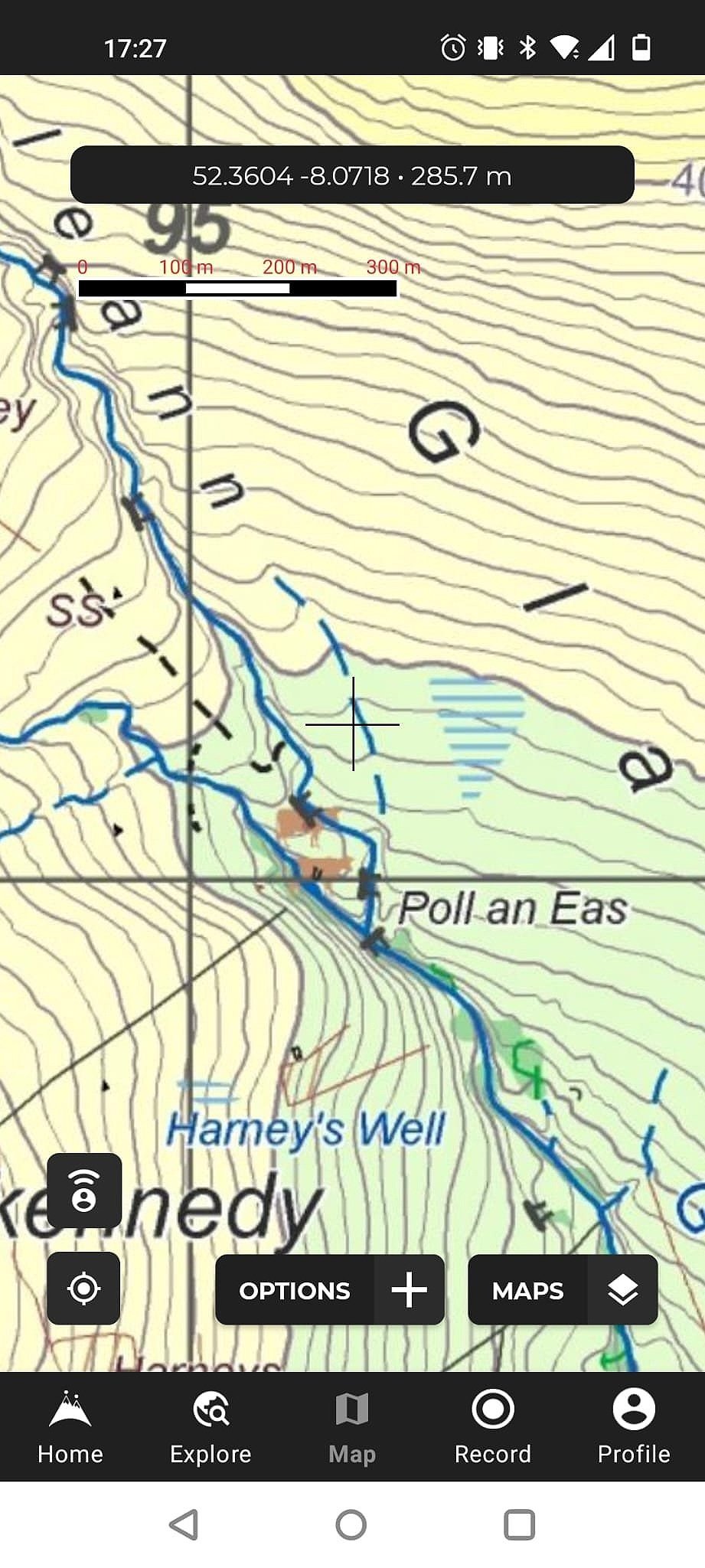

In the trio below, the first image shows the first two booley sites visited, one alongside the black fence on the right of the image, and the other on the far left. You can also see the pen through which I entered the open mountain on the top right of this first map image. The second and third images show the remaining four boolies that I hoped to get to on the same trip.

The blue circle on the far right of the overall map above was where I parked the car, in a small space just off a boreen. From there I walked just over a kilometre of trail with woodlands either side of me, before reaching the “pen” marked on the map. My entrance to the mountain was an intricate maze of gates and fencing, and it took three gates for me to escape into the open mountain.

As I left the final gate behind me, and eased up the gentle slope towards the first booley site, the irony wasn’t lost on me. In a similar journey to the one that cows would have made in the past, I was leaving the pen, symbolically leaving a more domesticated space, and moving up into the open hills. I almost felt as though I was retracing the very route that herders and cows might have taken at the start of summer in times gone by.

Once I had emerged from that final gate I stayed on a well-travelled trail alongside the fence, as the map showed the first destination was very close to the woodland’s edge. It was only about 700 metres or so of gentle walking before I had arrived. What I found there was a booley hut with its low walls still standing. Interestingly, the walls were completely overgrown with mountain grasses. Conveniently, the grasses overlaying the walls seemed to be a lighter shade than the surrounding grasses, which ensured that the hut was still fairly identifiable despite the overgrowth. I allowed myself ample time to study this scene from different vantage points, and thoroughly enjoyed the little dance I was doing with the sun in the process. The light was switching between moments of raw brightness when the sun did shine through, and a gloomy look when it slipped behind ominous grey clouds. My favourite resulting image was one in which I was able to marry the sun’s brightness with the sheer doom of the clouds hanging over the nearby hills.

Booley hut disguised in overgrowth

From there I headed west, traversing a boggy plain across largely flat land until I reached quite a healthy-looking fence. The next booley site lay across this fence, over the hill and then down the slope some way towards the Gleneereea river. I scanned north and south for a gateway, a stile, or even just a compromised strip of fencing where I might sneak myself across without damaging the farmer’s handiwork. I do not leave any trace of my having been in the hills, and all hikers should follow this principle. Thankfully, there was a “stile” of sorts, albeit an unconventional one, towards the southern corner of the fence. I cast my gear across first, before squeezing myself through.

The next site wasn’t a hut, but rather a collection of stones scattered in and on the ground. Experts have obviously decoded this to be a booley landscape, but my uninitiated eyes couldn’t connect the dots as I walked around the area. Perhaps there are some sources that will shed light on these kinds of sites. Here is an image of the most prominent rock at the site:

Evidence of booleying in Boolakennedy

Can you see the crack in the distant hill in the centre background of the image above? That’s roughly the heading I would have to take to reach the next site, though I would be dipping down below that height, to find two marked booley sites at a place called Poll an Eas, which translates to “the Hole of the Waterfall”. These sites were at a slightly lower altitude than where I stood at that moment. It’s fair to say there wasn’t much hard climbing today!

So, off I set towards Poll an Eas, following the river’s course, though I was travelling in the opposite direction to its water. The river looked refreshing beneath me, especially during the moments when the sun unsheathed itself from cloud. The weather couldn’t make its mind up all day. I spent some of the day in a t-shirt, and had even applied sunscreen before leaving the car, such was the clarity of the sunlight at that stage. Yet, I had to periodically scramble to put my jacket on when a sudden shower arrived. Mercifully, the showers passed quickly each time, and I would then have to instantly remove the jacket because it was such a clammy day.

Scene en route to Poll an Eas

When I finally reached Poll an Eas, I had to cross a narrow stream in a dyke and then climb up a steep bank on the other side to reach a small plateau. On the downslope between the plateau and the adjacent stream, a particularly large booley site sat cushioned into the slope. This must surely be one of the biggest in the range! Its entrance was on the river side, and its rear was protected by a steep rise. I found this building difficult to photograph, nestled as it is into the slope, and surrounded again by dead mountain scrub. It was also difficult to get far enough away from the building, whilst still keeping it in view over the grasses, and my limited selection of lenses didn’t help in that regard. Without wanting to bore readers with technical stuff, I have a fixed 40mm lens and a fixed 50mm lens, and that’s it. For the uninitiated, the view through a 50mm lens is more or less the same as the human eye. Even the 40mm didn’t offer me as wide an angle as I probably needed for this location. I would like to revisit it and spend more time there, perhaps coming up with a more interesting way of documenting it.

Booley site at Poll an Eas

Due to yet more socialising planned for that evening, it was time to bring the day’s adventures to a close. Unfortunately, I had to retrace my steps and head back to the car without visiting the other two marked boolies, which seemed to lie about 300 metres northwest of Poll an Eas. They would have to wait until my next outing.

Placenames as Historical Source

There is a townland just south of the Galtees called ‘Shanbally’, or “sean-bhaile”. The Irish phrase “sean-bhaile” means “old home” and suggests a place of permanent residence. Paradoxially, the classification of this town as a place of permanent residence actually draws attention to the fact that there were obviously more temporary dwellings in the nearby uplands. Eugene Costello believes that farmers living in Shanbally likely used the huts at Boolakennedy. (1)

Interestingly, Costello also finds evidence in the naming of streams and valleys in the surrounding area to support his argument. For example, he says that “the stream running down Boolakennedy is referred to in the mid-seventeenth century as the ‘brooke of Glaunary’ (Simington 1931, 363), which may be an anglicisation of Gleann Áirí, or ‘Valley of the Summer Milking-place’.”

Costello continues: “Furthermore, the Civil Survey calls the next valley to the east, at the eastern edge of Tubbrid civil parish, Glounbuollyneheneihy (Simington 1931, 363).” Costello suggests this is likely to be “an anglicised form of Gleann Bhuaile na hAon Oíche, ‘Valley of the One-Night Booley’. In Scotland’s Hebrides, the tale of the One-Night Shieling (Àirigh na h-Aon Oidhche) is very common in the body of oral tradition surrounding transhumance, and generally involves supernatural beings tricking and then murdering the occupants of a newly constructed summer shieling.” (“Shieling”, of course, being the Scottish term for a booley hut).

Costello believes this early-modern placename suggests that the folk tale may have existed in the Galtee mountains too. Indeed, he points to a record of these kinds of stories existing in other parts of Ireland, like Connemara and Mayo. “In any case,“ Costello summarises, “the ‘buaile’ element (in the placename) strongly suggests that Glounbuollyneheneihy was also used seasonally in the seventeenth century or earlier.” (2)

I feel it’s only right to point out that the notion of the term “buaile” referring only to summer mountain huts has been contested. Pádraig Ó Moghráin suggests this simplified understanding of the word actually undersells it, because in reality it had a multitude of meanings if you go back far enough. Ó Moghráin does concede that, “when used with reference to cattle it meant, primarily, an enclosure where cattle were kept at night and where cows were milked.” (3) Yet even this definition doesn’t confine it to summer huts only. It refers to any hut used for cattle at any time, thus not strictly tying it to the practice of booleying. Ó Moghráin argues that it is only in more recent centuries that its meaning was whittled down to focus solely on summer huts and herds. This merits reflection for anyone trying to glean historical insights from placenames, because it suggests that the roots of these placenames may have had subtler meanings at the time when those placenames started to come into use.

What’s Next?

Wild Camping! That’s right, you read correctly. I’ve finally decided it’s time to dip my toes into the world of wild camping. I’ve been gathering the gear in the past few months. I’ve been reading advice online. I’ve done trial runs in setting up the tent at home. In short, I’m ready! Or as ready as I’m going to be….

The test run in the back garden!

For my first outing in the wild, I’m planning to camp in and around Poll an Eas or thereabouts, with a view to being able to photograph the booley sites just northwest of there, which I obviously missed out on last time out. There’s a nearby water source, it’s a fairly easy location to access, and is at a relatively low altitude. I think these factors make this location a wise one for my first foray into wild camping. I can’t wait to report back to you next month, not only on the remaining Boolakennedy booleys, but also on my first experiences with wild camping!

Get in Touch

Please feel free to use the comments section below if you’ve got any wild camping advice, and historical insights, any questions around the photographic project I’m working on, or if you just want a chat. You can also reach me on email at hello@alantobinphotography.com. My Instagram handle is @alantobinphoto.

Thanks for reading, and we’ll chat again at the end of June.

Alan.

Sources

(1) Costello, Eugene. Transhumance and the Making of Ireland's Uplands, 1550-1900. Available from: VitalSource Bookshelf, Ingram Publisher Services UK- Academic, 2020. p. 114.

(2) Costello, Eugene. Transhumance and the Making of Ireland's Uplands, 1550-1900. Available from: VitalSource Bookshelf, Ingram Publisher Services UK- Academic, 2020. p. 114-115.

(3) More Notes on the "Buaile" (Pádraig Ó Moghráin and S. Ó D.) in Béaloideas , Jun. - Dec., 1944, Iml. 14, Uimh 1/2, p. 45. Published by An Cumann Le Béaloideas Éireann/Folklore of Ireland Society.